Categorías

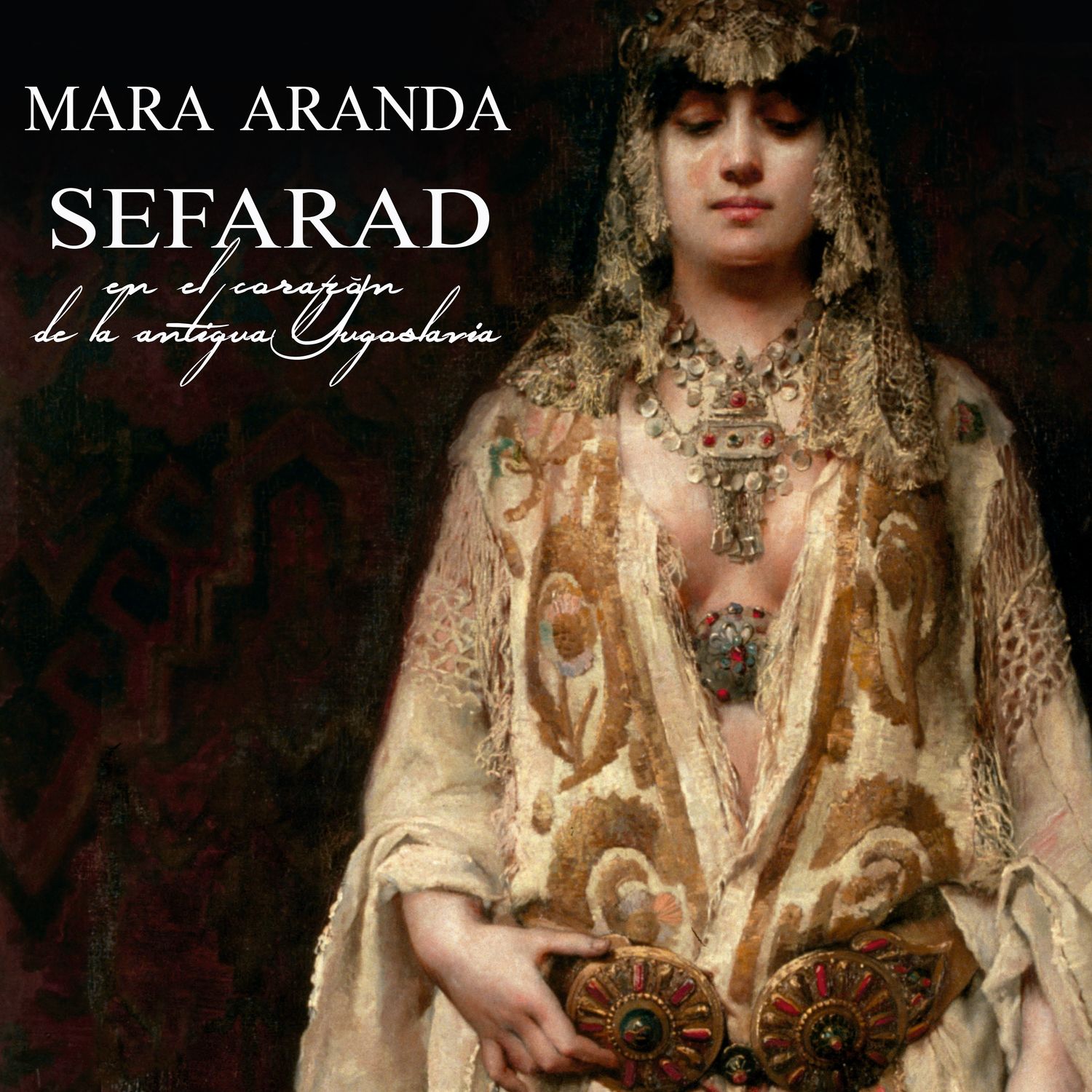

SEFARAD EN EL CORAZÓN DE LA ANTIGUA YUGOSLAVIA

REF 00003

€15.00

1

Información del producto

Debido a su larga historia de diversidad religiosa y cultural, a Sarajevo a veces se la llama la “ Jerusalén de Europa” o “Jerusalén de los Balcanes”. Es una de las pocas ciudades europeas importantes que tiene una mezquita, una iglesia católica, una iglesia ortodoxa oriental y una sinagoga en el mismo vecindario. Símbolo de esa multiculturalidad, es la Hagadda de Sarajevo, un manuscrito hecho en Barcelona en 1350, la cual pasó trances insólitos. Sale de Barcelona en 1492, con la expulsión, para dirigirse a Venecia donde sus dueños la vendieron sucesivamente hasta que en 1894 es adquirida por el Museo Nacional de Sarajevo en el año 1894. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los nazis quisieron apoderarse de ella, pero Dervis Korkut, director musulmán de la biblioteca del Museo, la dejó en manos de un amigo musulmán que la ocultó debajo de los tablones de madera del suelo de la mezquita. Durante la Guerra de Bosnia en 1992, el manuscrito sobrevivió a un robo en el museo pues los ladrones la dejaron sin saber de su valor. La Hagadá sobrevivió igualmente el asedio a Sarajevo por las fuerzas serbo-bosnias, oculta en la cámara acorazada y subterránea de un banco.

Convertida en un genuino símbolo de respeto y cooperación entre confesiones religiosas distintas, la inspiración de su historia y de sus ilustraciones se reflejan también en el presente disco. Valencian singer Mara Aranda concludes the sound pentalogy entitled: Geographies of the Diaspora initiated in 2017, with the present work: ‘Sepharad in the heart of former Yugoslavia’.

The journey has lasted almost eight years, resulting in the recovery of 65 unpublished or very rarely performed Sephardic songs, which cannot be understood outside the historical and cultural context of the Iberian Peninsula.

Because of its long history of religious and cultural diversity, Sarajevo is sometimes called the ‘Jerusalem of Europe’ or ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’. It is one of the few major European cities to have a mosque, a Catholic church, an Eastern Orthodox church and a synagogue in the same neighbourhood. Symbolic of this multiculturalism is the Sarajevo Hagaddah, a manuscript made in Barcelona in 1350, which went through some unusual events. It left Barcelona in 1492, with the expulsion, to go to Venice where its owners successively sold it until it was acquired by the National Museum of Sarajevo in 1894. During World War II, the Nazis wanted to seize it, but Dervis Korkut, the Muslim director of the Museum’s library, left it in the hands of a Muslim friend who hid it under the wooden planks of the mosque floor. During the Bosnian War in 1992, the manuscript survived a theft from the museum because the thieves left it unaware of its value. The Haggadah also survived the siege of Sarajevo by Bosnian Serb forces, hidden in the underground vault of a bank.

Turned into a genuine symbol of respect and cooperation between different religious denominations, the inspiration of its history and illustrations is also reflected in this album. Es un honor para mí componer el prólogo de ‘Sefarad en el corazón de la Antigua Yugoslavia’. Dedicaré este prólogo a sintetizar mi libro “Memoria intergeneracional y lengua de los sefardíes de Sarajevo” (2019, Palgrave Macmillan), en el que analizo la presencia de judíos de origen ibérico en los territorios que alguna vez pertenecieron al Imperio Otomano, luego a Yugoslavia y ahora a Bosnia y Herzegovina. Mi estudio ofrece una instantánea de la realidad sefardí en la actual capital de Bosnia y Herzegovina, Sarajevo.

SEFARAD EN EL CORAZÓN DE LA ANTIGUA YUGOSLAVIA

Mostrar precios en:EUR